Recent statements by Ali Shamkhani, senior adviser to Iran’s Supreme Leader and former secretary of the Supreme National Security Council, and Mahmoudreza Aghamiri, head of Shahid Beheshti University and a leading nuclear scientist, have reignited debate over Iran’s nuclear intentions. Both officials emphasized that Iran possesses the scientific and technical capability to build a nuclear weapon, while simultaneously asserting that the country does not intend to do so under current policy, citing Ayatollah Ali Khamenei’s religious decree (fatwa) prohibiting weapons of mass destruction. Yet both men also implied that this restraint is a matter of choice, not limitation, and that the fatwa “can change” should circumstances demand it.

Ali Shamkhani, speaking in the televised program Narrative of War, was asked whether he had ever considered pursuing nuclear weapons during his tenure as defense minister in the 1990s. His response was striking: “I wish I had thought about it… Today it’s proven that Iran should have built such a capability.” When pressed again, he added, “Yes, if I returned to that era, I would definitely pursue the bomb.” Shamkhani explained that the political atmosphere of the 1990s, defined by the reformist “Dialogue of Civilizations,” made such ambitions implausible at the time. His words were widely interpreted as a retrospective endorsement of nuclear deterrence, signaling that Iran’s leadership increasingly views nuclear deterrence as an asset for survival in an increasingly hostile environment - even if the current Supreme Leader does not appear to have shifted his view.

In a separate interview, Mahmoudreza Aghamiri echoed this theme of capability coupled with restraint. He declared that Iran “has the ability and possibility to build an atomic bomb” but “has no intention of doing so,” crediting Khamenei’s fatwa for preventing weaponization. However, Aghamiri also stressed that “a fatwa can be changed at any time, since it is the opinion of a jurist.” He elaborated that if Iran were forced into a confrontation — as he phrased it, “if they overturn the table, we will too” — the country would be ready to act decisively. His remarks underscored that Iran’s restraint is political, not technical.

Aghamiri’s interview also offered rare personal testimony about the twelve-day Iran–Israel war, in which he said six of his colleagues from Shahid Beheshti University’s nuclear physics department were killed. He described the chaos of that night, recounting how he was warned to flee his home amid missile attacks and later learned that several leading nuclear scientists, including Fereydoun Abbasi-Davani, had been killed. He insisted that despite these losses, Iran “still possesses the knowledge” to rebuild its nuclear infrastructure, claiming that the attacks targeted scientists rather than the Atomic Energy Organization itself. He rejected Western claims that Iran’s key nuclear facilities were destroyed, asking rhetorically, “If they truly destroyed everything, why can’t they let go?”

Throughout the interview, Aghamiri portrayed nuclear expertise itself as a form of deterrent power. “Simply having the technology is a deterrent,” he said, suggesting that nuclear knowledge grants Iran strategic leverage even without a weapon. He added that training students in nuclear physics inevitably includes understanding “how a bomb works,” and that “if the country ever needed it, everything could be done.” Such remarks reveal how Iran’s nuclear establishment frames its scientific achievements as both peaceful progress and implicit deterrence.

Both Shamkhani and Aghamiri framed Iran’s nuclear stance as a balance between religious principle and national security pragmatism. They reaffirmed that Khamenei’s fatwa forbids the use or production of nuclear weapons, yet both acknowledged the conditional nature of that ruling. Shamkhani’s retrospective statement — that he would have pursued nuclear arms had he known what the future held — and Aghamiri’s insistence that Iran has the technical ability to do so but chooses not to, together mark a subtle but significant rhetorical shift.

Their combined message projects dual signaling: to domestic audiences, that Iran remains committed to sovereignty and scientific independence; to foreign powers, that Tehran’s nuclear potential is real and restrained only by political and religious discretion. In an environment of renewed UN sanctions, intensifying Western pressure, and growing military tensions with Israel, these statements blur the line between reassurance and deterrence — reinforcing the perception that Iran stands on the threshold of nuclear capability, limited not by capacity, but by choice.

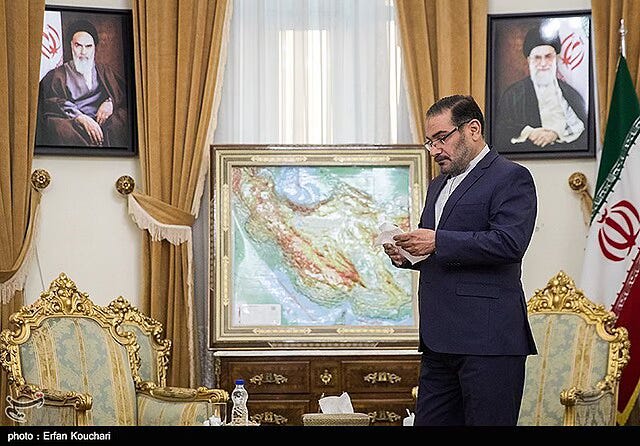

Photo of Ali Shamkhani courtesy of Wikimedia.